|

3. The Role of the Contemporary Teacher

It will now be clear that the role of the contemporary teacher

has essentially to do with something which is exceptionally

subtle and complex. The role of the teacher has always

been basically psychological in character, but the

dimensions that come to the view of the contemporary

teacher are much more difficult to deal with. It may be said

that the role of the teacher is not merely to promote the

quest of the knowledge of man and the universe, and the

sciences and arts of their inter-relationships. It is not also

merely to build the bridges between the past and the future.

These tasks are indeed important and they are entailed by

the perennial objectives of education. But what is so new

and so imperatively pressing is that the role of the

contemporary teacher is increasingly getting focussed on

the theme of changing human nature and that, too, on an

integral scale. In brief, what we are demanding from the

contemporary teacher is to inspire a change in the impulses

of the pupil's growing personality so as to foster harmonious

blending of knowledge, power, love and skills that are

relevant to the promotion of peace, co-operation and

integrality.

In order to bring out the implications of this role, we need to

analyse those assumptions of the teaching-learning

process which are directly related to deeper psychological

dimensions and operations. We shall refer to three most

important of these assumptions.

The first assumption is that teaching must be relevant to the

needs of the learner. The needs of the learner are varied and

complex. There are felt needs and there are real needs

which are not yet felt. There are needs of individual growth,

Page - 23

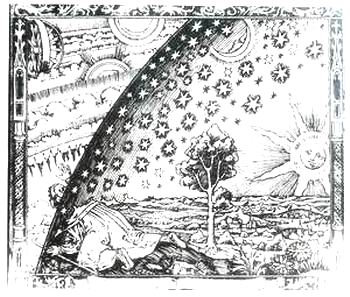

Curiosity

Page - 24

and there are needs resulting from the social reality of which

the learner is a part and in the context of which the learner

will be called upon to work and produce results so that the

wheels of social progress are kept in motion. There is also a

process of the growth of needs, some of which develop

spontaneously and harmoniously, while some others are

induced, not infrequently, by artificial means resulting in

temporary or permanent injury to both the learner and the

society. How to deal with this complex domain of the

learner's needs is one of the first tasks of the teacher. No

rules can be laid down or prescribed. For this domain

demands of the teacher a good deal of observation of the

learners, a sound and sympathetic knowledge of

psychology, and practical insight and tact. The task is at

once easy and difficult depending upon the natural or

acquired capacity of the teacher to relate contents and

methods of learning to the felt needs of the learner. Much

will also depend upon the facility with which the teacher is

able to consult the learner in his growth, and to enthuse him

to make the necessary effort to bridge the gulf between

what is desired and what is desirable.

The second assumption is that teaching should provide

learning experience to the learner. Sometimes, the stress

laid on learning experience is so exclusive that the role of

teaching is reduced almost to vanishing-point. At the other

extreme, learning experience is conceived to be so

overwhelmingly dependent upon teaching that the

teaching-learning process is reduced to a process of

spoon-feeding. These extreme positions, however, bring

out the complexity and subtlety involved in the interaction

between the teacher and the learner.

There is no doubt that the greater the preparedness and

motivation of the learner, the greater will be the intensity of

the learning experience. The minimum that is required of the

learner is curiosity. But the teacher can play a major role in

intensifying the initial curiosity and in developing in the

learner a sense of wonder which is not only a great propeller

of learning but also a constant flower and glow of learning. It

is true that sincere dedication on the part of the learner is the

golden key to learning, but here, again, the teacher can play

a major role in kindling the inmost spirit of the learner which

is the unfailing source of sincere dedication.

It is also necessary to note that every learner has certain

innate reflexes, impulses, drives and tendencies, and the

teacher can uplift them and help the learner in transmuting

reflexes into organized perceptions and acts of behaviour,

innate impulses and drives into wise and skilful pursuits of

ends and means, and innate tendencies into a harmonious

and integrated personality. In fact, it is this process of

transmutation that is the heart of learning experience, and it

is this experience that gives to the learner the art of learning

to learn and learning to be.

The third assumption of teaching is that it accelerates the

learning process. Here, again, the role of the teacher is

complex and difficult. In general terms, it can be said that

the teacher is an accelerator of human progress. But in his

day-to-day work, the teacher realizes that different students

or different categories of students have different rates of

progress and that it would be unwise to impose the same

degree of acceleration on all the students uniformly. To vary

the rhythm of progress in accordance with the requirements

of the learner is one of the most delicate tasks of the teacher.

More than ever, the role of the contemporary teacher will be

to uplift the knowledge and effort of the learner by ,

suggestion, example and influence. His task will be not to

impose but to suggest and inspire. He will respect the

psychological combination of the tendencies of the

learners, and he will endeavour to improve them not by

hurting or crushing the force of these tendencies but by

refining them, by recombining them and by training them to

achieve their maximum possible excellence. At the heart of

his dealing with learners, the teacher will aim at leading

them from near to far and from the known to the unknown

by providing to them the required exercise of thought,

imagination and experience. And, in doing so, the teacher

will share his experiences with learners, and interweave his

own development with their development.

The teacher will not underrate the importance of the

Page - 25

Page - 26

development of any particular aspect of personality. For, all

aspects are important, and even when one is not competent

in regard to any particular aspect of the totality of

personality, there should not be an attitude of negligence or

derogation towards that domain. There is, for instance, a

tendency among many to look down upon physical

education and to advocate the training of the mind in

preference to the training of the body. In a balanced view,

however, the training both of the mind and of the body is

necessary. A healthy mind in a healthy body is the ancient

advice of the wise. A good teacher will always encourage

the learners to participate in a methodical and well-designed

programme of physical education. It is true that sometimes,

physical education is looked upon as a mere pastime and a

matter of recreation rather than as a discipline closely

related to the perfection of human personality. A good

teacher will therefore promote the right conception of

physical education and will lay a special emphasis on it so

that the learners are encouraged to develop health,

strength, agility, grace and beauty by means of disciplined

practice of any preferred system of physical education. A

good teacher respects the ideal of sportsmanship and

encourages the qualities that are associated with

sportsmanship, such as courage, hardihood, initiative,

steadiness of will, rapid decision and action, good humour,

self-control, fair play, equal acceptance of victory or defeat,

loyal acceptance of the decisions of the referee, and habit of

team work.

Development of personality and, particularly, the process of

change and integration of personality, cannot truly or

adequately be effected without the pursuit of values. For as

we have noted earlier, corresponding to each faculty or

capacity of personality there are values, and children, right

from early stages, manifest their urge towards values

through admiration and aspiration. Very often educators do

not recognize these manifestations, and, in due course, for

want of encouragement and recognition, they become

diminished and even begin to be wiped out. It is therefore

very important that educators observe children deeply and

sympathetically, feel themselves vibrant with children's

aspirations and encourage them.

The most important quality that should be focussed upon is

sincerity. It is the one quality which, if rightly cultivated, will

necessarily enable the child to realize whatever aim he

comes to conceive and pursue in his life. And around this

central quality, we may conceive of certain groups of

qualities that come into play at various stages of the

psychological development of the child. There is, for

instance, a trinity of qualities of heroism, endurance and

sacrifice, which are essential for the lasting victory of the

good and the right. There is also a trinity of cheerfulness,

cooperation and gratitude, which are, we might say, the

secret of all right relationships. Another trinity of qualities

that can be mentioned is that of purity, patience and

perseverance, which is indispensable in surmounting any

weakness or limitation of our nature. And, finally, we may

note the trinity of calm, profundity and intensity, which open

the doors to an ever-progressive search of perfection.

It is sometimes suggested that value-oriented education is

relevant only to the primary and secondary stages, but not

beyond. For, it is argued, children by the time they complete

secondary education would have already formed their basic

attitudes and traits of personality, and nothing more needs

specially to be done in that direction at the higher levels of

education. But this argument misses the point that the

important element in value-oriented development of

personality is the development of learner's free will and of

his free and rational acceptance of the value-system and

directions of the growth of personality. And this

development can rightly be done only at the higher level of

education, when the learner has developed a will of his own

to some extent and when he has basic intellectual and

moral and aesthetic sensibilities enabling him to examine

the basic values and aims of life.

It is often asked if the role of the teacher includes anything

more than that of teaching. At higher levels of education, it is

universally recognized that the tasks of research and

extension should also be included in the role of the teacher.

At the school level, the task of extension is being gradually

recognized, particularly, in the wake of the realization of the

close connection between education and development. In

Page - 27

this context, the role of the teacher as community teacher

must also be recognized. And, we might suggest that, while

research as understood in the technical sense of the term

may not be included in the role of the school teacher,

progressive updating his knowledge and skill must be

included.

The role of the teacher in the context of the goal of

education for all, of life-long education and of learning

society needs to be emphasized. The teacher will reject the

view that only a few should climb to the heights of

knowledge, culture and development while the rest should

remain for ever on lower ranges of development. Following

the cry of the greatest leaders of mankind who have striven

to regenerate the life of the earth, the teacher will help

spread knowledge not merely for a few but for all, and he will

emphasize the programmes of universalization of

elementary education, of adult and continuing education,

and indeed of the learning society. Corresponding to the

needs of multi-faceted development, the teacher will

promote education in every sphere of developmental

activity. He will also help forging links between formal and

non-formal education, and assist in a wide variety of

educational programmes which can be made available to

growing number of students of all ages.

The most significant symbol of learning is the child; and the

learning society will acknowledge the sovereignty of the

child. It will hold the child in the centre of its attention, and

will bestow upon it the supreme care that it needs. It will

organize all activities in such a way that they become

vehicles of the education of the child. Just as the child

always looks to the future, even so the learning society will

constantly strive to build the paths of the future. Just as the

child will grow increasingly into vigorous and dynamic

youth, even so the learning society will continue to mature

into unfading youth. To actualize such a learning society is

the responsibility of all thinking members of the society, but

increasingly and progressively it may come to be regarded

as the over-arching responsibility of the contemporary

teacher.

|